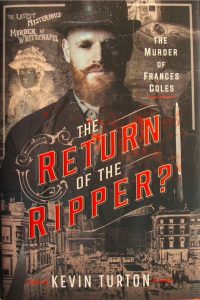

I’ve just been looking over my research for the last book – Return of the Ripper? The Murder of Frances Coles – and it got me thinking, not about who the Ripper was but about how he managed to escape being caught. Out of all the murders, and for the uninitiated there are believed to be 5, he walked calmly away into the night unseen. Question is how? I mean how does a serial killer, particularly one operating on the streets, kill, mutilate and disappear?

In the book I examined the cases, the modus operandi, the investigation etc which gave me an overview of just what Whitechapel’s police were up against back in 1888.But I never gave too much thought as to how he got away with it. I was writing about a murder on the periphery of the Ripper era so had other priorities. But recently I have had to look into the death of Martha Tabram, a disputed Ripper case, and that made me begin to question what we know about this man and how he operated. Tabram is, as far as I am concerned, his first, I think even though she was killed differently she has all the hallmarks of our friend Jack. For me she marks the start of a killing spree that gripped the world and began the evolution of modern policing. At that time there was no such thing as crime scene photography, or crime scene protection. There were no forensic teams, no understanding of murder, no profiling suspects and no police strategies designed to aid officers in any follow on investigation. But from her murder in August 1888 and those that followed, systems, and procedures, began to evolve. Police learned the importance of the crime scene itself, what it reveals, what it hides, how it unfolded and in some cases why. Examining doctors began to realise the importance of detailed evidence, what that evidence revealed and why it was paramount in the follow on enquiries. They also learned, though very slowly, just how vital calculating time of death was to the investigating officers in trying to place a killer at the scene. So, from her appalling death on the landing of St George Yard Building came an understanding that crime scenes tell stories.

What they don’t necessarily tell is the who, and the why, of the murder itself. That’s what got me thinking.

We all know Jack the Ripper, the top hat, cane, cloak, dark night, cobbled street killer who was never seen, never heard and never caught.

Question is why?

By the time of Catherine Eddowes killing in Mitre square 29 September police should have had enough clues to pin him down and if they couldn’t catch him at least ensure it was impossible to strike again. But they didn’t. Despite a heavy police presence on Whitechapel’s streets, a growing knowledge and local understanding of the growing dangers of being out in the early hours of the morning, and descriptions of varying quality published almost daily, he continued to kill at will. So, why was that possible?

When I was writing about Frances Coles, a murder 3 years after the carnage of 1888, that question still puzzled me.

Over the years there have been numerous suspects. To my mind none of them fit. Oh they could have been around, maybe even questioned, who knows? But they don’t feel right, can’t explain why maybe it’s because my notion of who Whitechapel’s serial killer was is different to everyone else’s. For me JTR was a sailor, a merchant navy man if you like, a man who lived by the tides and the voyages in and out of London docks. Recent research into a different subject gave me the opportunity to look into the types of vessels operating out of London in the 1880’s and the voyages they made. Intriguingly, leastways for me, I found those that did the distance runs, Chile, south America, New York and so on created the best opportunities. What I mean by that is that the crews that made up these ships, all which were often made up of men that had been sailing up and down the channel between long distance voyages, were men familiar with Whitechapel. Often these sailors used the local doss houses scattered all around the district, disappeared for a week or so then maybe took on voyage south, say to Chile, and were then absent for six to nine months. Perfect cover for a serial killer. Look at the so called canonical 5, end of August through to end of September, five weeks or so then nothing until November then nothing again until July 1889 and Alice McKenzie. Perfect sailing times. Oh, I know she’s not seen as a Ripper killing but everyone except the examining doctor thought she was.

Food for thought? One other point before I close. Do you really think Jack took organs from his victims? If he did how? I mean how did he carry them away? There were no plastic shopping bags back then there were no mobile ambulances either. The point being organs could well have been lost well before the autopsy.

In February 1891 Jack the Ripper returned, or did he?

In February 1891 Jack the Ripper returned, or did he?